Attachment Theory was originally developed by John Bowlby to describe how human infants look to form attachments with adults from which they can experience security and comfort.

Bowlby, a British psychologist, psychiatrist and psychoanalyst developed a strong interest in child development and understanding experiences of separation after being extremely affected by the loss of his nursemaid and being sent to boarding school during his early years.

During his career, Bowlby was most interested in finding out what caused children to develop strong bonds with people and discovered that children are biologically ‘wired’ to form attachments with adults in their immediate surroundings to increase their chances of survival. The child will develop a set of behaviours to keep their familiar caregiver close. These behaviours are especially noticeable in the face of perceived or real threat.

His research was further developed when Mary Ainsworth (01.12.1913 – 21.03.1999) began observing early emotional attachments between children and their primary caregivers and developed what is widely known as the “Strange Situation” procedure. In this observation, children undergo two short periods of separations and re-union with their caregiver as well as contact with a stranger.

In her experiments Ainsworth discovered that children will have different patterns of attachment depending on how they experienced their early caregiving environment. Depending on how they reacted to the events during the “Strange Situation”, children were placed into three different categories: secure, insecure-avoidant and insecure-ambivalent attachments.

Ainsworth’ research was extended by one of her doctorate students, Mary Main (born in 1943) who discovered the additional category of disorganised attachments, in which children show a lack of attachment behaviours, replacing them with a strong need to be in constant control of the situation.

These days, attachment theory is widely used in the study of infant and toddler behaviour, as well as infant mental health, treatment of children and related fields.

Attachment Behaviours

Humans are generally very social beings, so it’s no surprise that most people look to form relationships with others in their lives. Everybody forms affectional bonds with a range of people throughout their lifetime, people who we like to spend time with and for whom we have positive feelings.

Attachment Theory finds its importance in the ability to guide our understanding how children develop and form close relationships. Often their very earliest years are critical for their later development and ability to develop trust in others, as well as self-reliance, positive expectations of themselves and people around them and overall confidence.

Attachment Theory suggests that children form strong bonds with adults in their immediate environments to increase their chances of survival.

This can easily be understood if one looks at the helplessness of a newborn – the newborn is completely reliant on adults to take care of them and is therefore looking for ways of increasing their chances that this will happen reliably.

The attachment bond is therefore a special form of relationship that is seeking to experience security and comfort from one person to another.

The child develops a set of attachment behaviours that are meant to keep the caregiver close in order to create a secure base from which they can go on to explore the world. These behaviours will be activated whenever the child feels threatened with separation, physical rejection or alarming conditions in the environment.

These behaviours are

- Proximity Seeking

- The child wants to be physically close to the caregiver

- Separation Protest

- The child doesn’t want the caregiver to leave and will protest if this happens or is likely to happen

- Secure Base Effect

- The child will happily explore surroundings as long as the caregiver is close by

Examples of all of these behaviours can easily be seen on close observation of young children in their daily environments. A child may appear glued to their parents leg when entering an unknown situation like a new school or activity (proximity seeking), protest and be very vocal about their caregiver leaving (separation protest) or be playing further and further away from the caregiver before realising that they are out of sight, which will then often lead to looking for and quickly returning to the caregiver (secure base effect).

Children can form attachments with a number of adults, however one of them will most likely be the child’s primary attachment figure.

Exploration Behaviours

Humans are naturally quite curious creatures and so it is no wonder that as the child is getting older and develops the ability to crawl, walk, talk and ask questions they start to explore more and more of their surroundings.

New things in the environment will trigger our innate sense of curiosity as we try to figure out whether they might be of benefit to us. This can easily be observed in children that are placed into a new situation, such as a waiting room or a new playground.

At first they might show signs of uncertainty and stick close to their caregiver while carefully examining their surroundings for anything that could potentially be dangerous. But if the situation proves to be relatively calm and the caregiver shows no apparent signs of distress, they will often venture out and start interacting with whatever they can get their hands on: books, toys, magazines, anything goes.

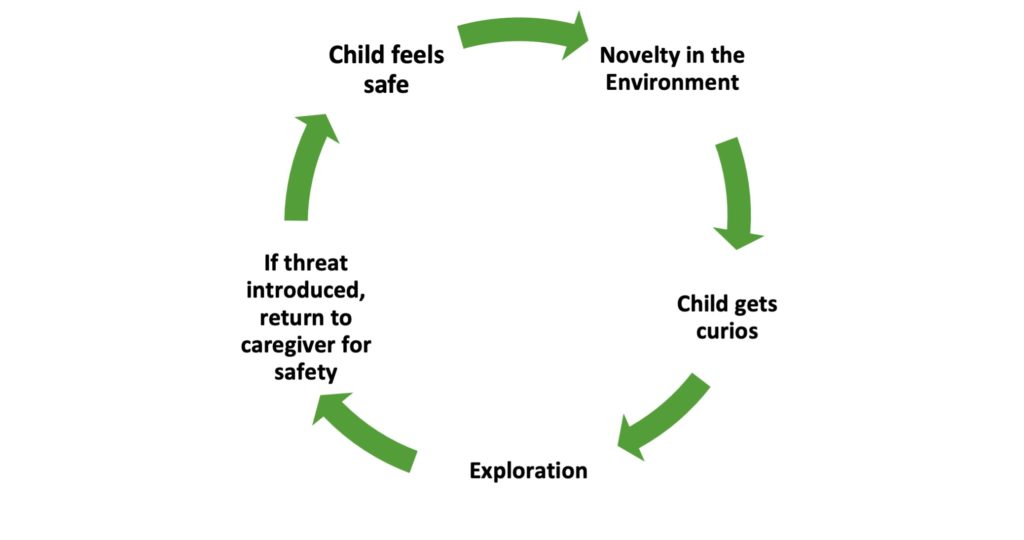

Attachment Theory suggests that if the child feels safe enough through presence of their attachment figure and a lack of alarming conditions in the environment, the child will go and curiously explore. If however a threat is introduced (like a stranger walking in, loud unidentifiable noises, the caregiver leaving, etc.) the child will quickly look to return to their attachment figure for security.

Attachment and Exploration

As children grow older and develop their abilities to interact with the world they look to balance their needs for attachment security with the strong urge to curiously explore their immediate and wider surroundings.

If children are provided with a sensitive and responsive relationship with one or several sensitive and responsive adults, they will have a secure base that is available for support and comfort. Children will know that it will be available to them if needed, which increases their confidence in going out to explore new things and interact with the outside world.

It is easiest to imagine this as a type of balance between the need for attachment and the need for exploration; when things are frightening, the attachment need will activate and drive the child to seek increased safety and security through closeness to their primary attachment figure; when things are calm and safe, the child will begin to curiously explore and look for novelty in the environment.

a fine balance

In a safe and secure relationship, this balance is provided by caring adults in the child’s life that are available and support both of those scenarios.

Imagine a child that runs around on a playground, curiously exploring all the different ways of having fun. The parent sits on a bench close by and the child, looking over his shoulder, realises that he has nothing to worry about as he can still see the parent even if he walks away a little further.

The child tries to jump over a little stump sticking out of the sandpit, but unfortunately his foot catches and he falls over, badly hurting his knee in the process. He runs back to the parent, crying, holding his knee, looking for comfort and the parent that has seen the situation unfold, reacts with kindness and warmth, gently examining the wound while comforting and reassuring the child that he has indeed hurt himself, but will be okay.

After a little while, the child calms down and, if the injury isn’t too serious, will most likely run off again to play some more.

What has happened here? The child experienced a secure base by knowing that the parent was close by and therefore felt that it was safe to engage in curious exploration of his environment. But unfortunately the exploration is interrupted by the introduction of something that is rather uncomfortable; in this case, physical pain drives the child to return to the parent as the need to experience security and comfort through the attachment figure is increased. The parent takes care of the child and therefore meets the child’s attachments needs, which in turn will increase the child’s feelings of safety. Lastly, the child returns to a state of feeling safe enough to once more go out and curiously explore.

To summarise:

Children in secure relationships are able to balance their need for experiencing security and comfort through attachment figures with their strong sense of curiosity and drive for exploration as the adults who take care of them allow for both of these needs to be met.

If the child’s needs for attachment and/or exploration aren’t met, they can ‘tilt’ towards either side of the scale, or completely replace both of those needs with the strong need to be in constant control of the situation they find themselves in. You can read more about these insecure types of attachments and their impacts on children as they grow and develop in my follow up article here.